Daily reminders in the form of emails from the University of Edinburgh inform me of vast numbers of presentations, training workshops, seminars, support opportunities and social events. Mostly I let them flow past me, quickly scanning to determine the relevance, the majority ending up deleted, but occasionally I get a tinge of FOMO. It would be fantastic to avail of some of the training on campus and/or the interesting guest seminars every now and again. After a discussion about trying to find a good time to get over to be ‘present’ for a few days, I debated different options, then an email popped up about the annual writing retreat in June. This is in the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh no less – decision well and truly made. So hopefully I will fill that post with flowers galore, I am so excited and fear that the distraction potential will be pretty darn high, but seriously what a luxury to have an entire day for writing.

My recent reading, linked from the previous post, is Medical Humanities and Medical Education, How the medical humanities can shape better doctors by Alan Bleakley. Specifically, chapter 5 Towards a medical aesthetics Creativity and imagination in medical education. Firstly, it is the first time in my background reading that many threads are starting to come together. Within a few pages familiar authors such as Lippell, Ness, Salmon, Young, McWilliam, Csíkszentmihályi, Charon were all coming together in one place. It considers ‘creativity’ to be weasel word which is just perfect (thinking at this point reflection is also a weasel word in meded). My line of thought is swirling around creativity, fiction and reflective practice – slowly, ever so slowly creeping towards a research question. Creativity can be approached as a product, process or person. For me it is the process aspect that has attracted me over the last few years and what I have been exploring in my LEGO® Serious Play® work and activities such as #ds106, where the product is almost an aside.

I'm now seeing weasels all around @architek2ra pic.twitter.com/EKTOsRgW0A

— Clare Thomson (@slowtech2000) May 8, 2019

Bleakley speaks of reflective practice, pointing out that since the end of the last century he has warned about taking an overly simplistic interpretation of Schön’s work (1991) – warning “… against ‘reflective practice’ becoming a mantra, often invoked but rarely authentically practiced.” – something I have debated in my papers so far (page 106-107). Also now I need to read that 1999 piece: From reflective practice to holistic reflexivity.

There is also an interesting paragraph about medical education privileging complicated over complex. Here Bleakley posits complicated as consisting of many discrete linear elements which neatly fit together into a whole, the whole being a sum of all the parts. In contrast complex is dynamic and non-linear and the resulting whole is more than the sum of the parts (page 117). In other words complexity acknowledges and embraces the mess. Medical education is not currently embracing this mess (note to self this is also relevant for another project).

The remainder of the chapter outlines a list of ten different ‘typologies’ of creativities, from process to creativity as resistance to the ‘uncreative’. I will definitely be coming back to this chapter again as the notes here only touch the surface with Jazz, improvisation, hierarchies, power, democracy, authoritarian systems and much more discussed.

From Bleakley I then arrived at the work of Roger Kneebone who directs the Imperial College Centre for Engagement and Simulation Science (ICCESS) and has a large body of work centred on performance as a positive attribute of medical education and beyond.

Yet because clinicians are reluctant to think of themselves as performers they often miss opportunities to share their experiences with people outside medicine or science yet framing one’s work as performance can be very helpful. … When I was doing surgery in the 1980s I focused more on the preparation and delivery, about studying and operating than on reflection or recovery. I hardly ever thought about recovery I think, about learning when things went wrong without losing my confidence and nobody spoke at that time about reflective practice. Yet that kind of reflection is what being a performer requires, because it’s there that the most effective learning takes place.

Kneebone, 2018

Next I came across John Launer, who is also passionate about narrative medicine and have added his book to my list: Narrative-Based Practice in Health and Social Care: Conversations Inviting Change. Then I discovered he had interviewed Roger Kneebone in a podcast – each thread weaving with another: Dr John Launer in conversation with Roger Kneebone.

Following each thread from paper to book, to website, to paper is time consuming but rewarding. During this reading element I’m trying to enjoy what Dr Charles Anderson put beautifully, in a presentation stored within Blackboard (a rich online source of help and advice), note emphasis is mine:

deepening and extending knowledge and insights; playful exploration of ideas and disciplined analysis

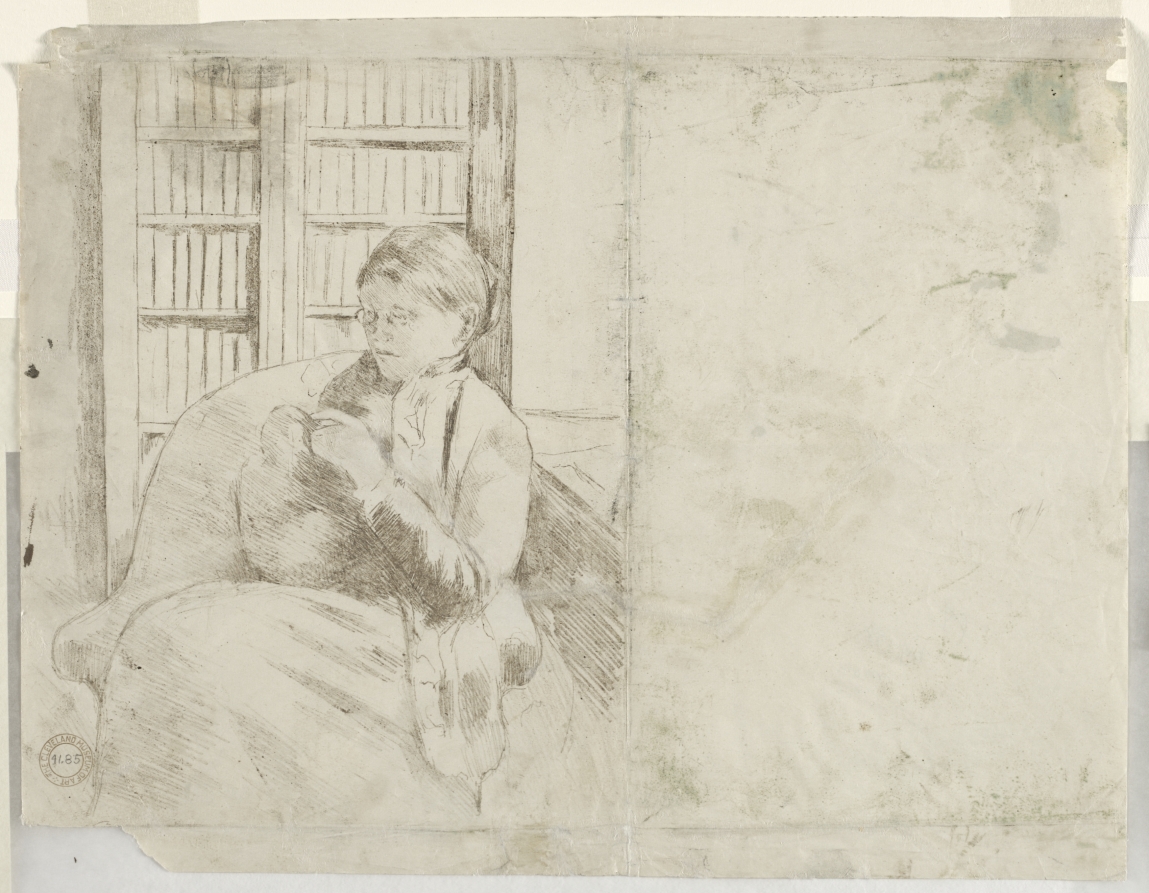

Featured image: Knitting in the Library (verso) (CC0)

References

Bleakley, A. (2015). Medical humanities and medical education.

Kneebone, R. (2018). Performing Medicine, Performing Surgery. Available at: https://youtu.be/d70PSDlYmTw [Accessed 13 May 2019].

Schön, D. A. (1991). The reflective practitioner How professionals think in action. Aldershot Ashgate Publishing Ltd.

Leave a Reply